Burnham’s Building Back Buses blueprint: bringing buses back under public control give cities a chance to reverse one billion lost journeys

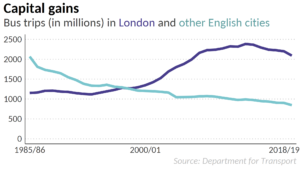

- Between 1986 and 2019 – the last year before the Covid epidemic hammered public transport – the number of bus journeys in metropolitan areas outside London fell by more than half, from more than two billion a year to fewer than a billion, according to analysis by Be The Best Communications’ People, Places, Policy and Data Unit.

- London never lost control of its buses, and its buses thrived. In 1986, for every one bus journey in the capital there were 3.5 in other parts of England. Since 2011/12 there have been more journeys in London than in the rest of England put together.

- Despite this London is far less reliant on the bus than places like Greater Manchester. Outside London, for most people, public transport means buses.

- At the time of the last Census, nearly three times as many commuters living in Greater Manchester used the bus to get to work as used the train or tram. In London, for every person commuting by bus there were 2.5 using the tube, train, or light rail.

It was, said Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham, the “green light to deliver a London-style public transport system”.

Last week, the Royal Courts of Justice delivered a landmark ruling, rejecting an appeal by two bus operators and siding with Mr Burnham in his plans to bring buses back under public control.

Greater Manchester will now become the first city-region outside London that can set its own bus timetables and fares – with mayors in other parts of the country lining up to follow suit.

Mr Burnham hopes to “develop a blueprint” for other city-regions to follow when it comes to connecting cities, town and villages by bus.

The “green light” has been a long time coming. Even before the Bus Services Act 2017 gave metro mayors the power to introduce franchised services, council leaders in Greater Manchester had been trying for years to use earlier powers – such as Quality Bus Contracts, a provision of the Transport Act 2000 – to introduce forms of regulation.

These proved fiendishly complex to plan, fund or deliver – let alone integrate into a network including both train and tram.

Even the new powers available to metro mayors have taken years to bring to fruition – and franchising in Greater Manchester won’t happen overnight, but will be rolled out across the 10 constituent boroughs over the next three years.

The well-publicised flat-rate fares – of £2 for a single adult journey anywhere in Greater Manchester – won’t happen anywhere until autumn 2023.

Mr Burnham has been careful to stress that his court victory is only the first step in building a transport system that works for the people of Greater Manchester. And with good reason: having the powers in one thing, but having the money to use those powers is something else.

The tram network in Greater Manchester has its own, complex and arguably expensive, ticketing system. The train network is nothing like London’s. And neither are the buses. Mr Burnham is going to have to build up from a low base. That won’t come cheap.

Before 1986, bus services across the UK were regulated by local authorities. That year saw the Transport Act 1985 come into force. It abolished road service licensing and allowed private companies to compete to run profitable routes, with no expectation the surplus would be used to pay for less popular (but still vital) routes elsewhere. Local authorities could choose to subsidise these routes through other means – but without income from the profitable routes, struggled to do so.

The aim of this mass privatisation was to increase competition and lower fares. There is some evidence it did so in very specific urban areas where demand was highest.

In some cases this competition has reached absurd heights: in Manchester itself, in 2007, the city centre ground to a halt as bus companies flooded the route from West Didsbury to Piccadilly with 30 buses an hour. Eight trams became stranded in the queues and Metrolink rush-hour services were cancelled.

In other areas, though – including other parts of Greater Manchester – services were reduced or scrapped, and local monopolies emerged over those routes which remained.

The numbers, analysed here by Be The Best Communications’ People, Places, Policy and Data Unit, speak for themselves. Theyshow that between 1986 and 2019 – the last year before the Covid epidemic hammered public transport – the number of bus journeys in metropolitan areas outside London fell by more than half, from more than two billion a year to fewer than a billion.

“Outside London” is key, because London was the one city that was exempt from deregulation. London never lost control of its buses, and its buses have thrived. In 1986, for every one bus journey in the capital there were 3.5 in other parts of England. Since 2011/12 there have been more journeys in London than in the rest of England put together.

Yet it wasn’t merely the fact that London kept its ability to regulate services that saw bus use boom. Rather, it was what London did with that ability.

Bus use in London remained fairly flat until the capital chose its first directly-elected mayor in 2000. Ken Livingstone then oversaw a major injection of cash into the system and introduced a £1 flat rate for fares. Subsidy has remained high since then – “hopper” fares which give unlimited travel for an hour, however far the journey, remain at £1.65 for adults.

As a result the number of bus journeys in London rose from 1.3 million a year in 2000/01 to 2.2 million a year in 2008/09.

The London mayor’s ability to subsidise local routes has created a huge asymmetry between the capital and the rest of the country. Across England, local bus services have received an average of £848 million per year from national and local government since the turn of the century. London services have received an average of £539 million per year – or nearly two-thirds of the total (services in Greater Manchester received an average of £33 million, for the record).

London’s control over its public transport gives it other important advantages, too: chiefly, the ability to implement a smart payment system that covers multiple modes of transport. It has also built up a genuine multi-mode network, where trips between any two points make logistical sense. Greater Manchester lags far behind: its Metrolink tram system, while expansive, has no circle line but rather operates on a “hub and spoke” model which prioritises getting people into (and out of) Manchester city centre.

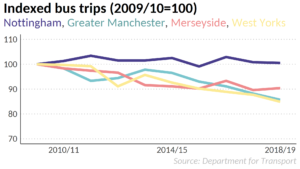

Meanwhile, bus journeys within Greater Manchester had been falling year-on-year even before Covid struck. In 2013/14, there were 216.0 million bus journeys across the city region; by 2018/19 that had fallen to 189.2 million, a drop of 12.4 per cent. (2020/21 the number plummeted to just 68.5 million as the country saw repeated pandemic lockdowns.)

Greater Manchester wasn’t alone in seeing waning bus use in the second half of the 2010s. Merseyside saw bus journeys fall by 1.4 per cent 2013/14 and 2018/19, while the West Midlands was down 5.8 per cent, Tyne and Wear by 8.0 per cent, West Yorkshire by 11.2 per cent and South Yorkshire by 16.0 per cent.

London has seen a fall-off since 2013/14, too, by 7.8 per cent – but that followed decades of growth. By the end of 2018/19 there were 12 bus journeys in London for every one in Greater Manchester, despite the fact the population of London is only three times greater. This isn’t a failing of buses in Greater Manchester in particular – rather, it reflects the buses succeeded in London when they were failing everywhere else.

It is ironic therefore that London is far less reliant on the bus than places like Greater Manchester. Outside London, for most people, public transport means buses.

At the time of the 2011 Census, nearly three times as many commuters living in Greater Manchester used the bus to get to work as used the train or tram. In London, for every person commuting by bus there were 2.5 using the tube, train, or light rail.

And despite the bus being the only public transport option for large swathes of Greater Manchester, many don’t consider it a viable one: at the time of the 2011 Census there were six people travelling to work by car for every one using the bus (in London far more people take the tube or train than drive).

Still, though, the court case was a major first step in setting things right. And there is evidence from other parts of the country that a lot can be achieved with relatively little money. Nottingham, for example, has retained a degree of control over its buses by owning the majority of the company that operates most services in the city. By law, the company operates at arms length from the council – but the council does have representation on the board, as does the wider community.

Bus routes in Nottingham are planned on a city-wide basis, and part-subsidised with a workplace parking scheme which generates money and helps take cars off the road, creating more space for buses. It is notable that Nottingham has largely preserved ridership levels over the last decade, while they have fallen in other cities.

Mr Burnham knows he needs money to deliver similar improvements, let alone to achieve his vision of a “London-style” network. He has outlined a £1.2 billion, five-year investment programme that includes £430 million to improve buses. The funding comes from various pots – including a share of Boris Johnson’s £1 billion “Bus Back Better” fund, and money promised in the spending review – some of which are more secure than others. The £135 million needed simply to move to a franchising model has come from council tax rises and contributions from cash-strapped local councils.

Mr Burnham has also hired Vernon Everitt, who spent 14 years as managing director of Transport for London, to oversee work to make the bring the so-called “Bee Network” to life. Mr Burnham could hardly have a better driver, and the road ahead is now clear; but there is a very long way to travel, and if Greater Manchester is going to get there then ultimately the government is going to have to stump up to put fuel in the tank.